|

glass notes photo library shop windows |

| previous page |

| e-mail us |

![]()

![]()

cleaning & restoring glass

| N.B. While we believe all the information provided on these pages to be correct, we cannot be held responsible for any damage arising out of the use of any of the cleaning, repair and restoration techniques described, which are used entirely at the reader's own risk |

![]()

page 2: restoration

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

|

general rules

There is, of course, no absolutely right or wrong way to go about making repairs to a piece of glass. If it comes out well, you did a good job. If it looks worse than it did before, well ....

Here's some advice that may prevent the air around you turning blue:

If you bite the bullet and stick with it, you may even turn out to be a good glass repairer - I wish you the very best of luck!

|

![]()

|

satinised or frosted glass

One problem with satinised or frosted glass items (as stated on the previous page) is that the rough surface (being effectively like a whetstone itself), if knocked against a metal object, can pick up metallic smears and scuffs which are hard to shift by normal cleaning methods

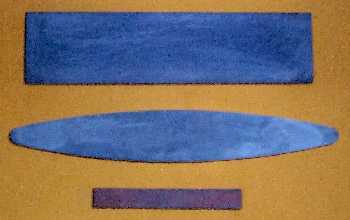

If, having tried all the normal methods, you find this to be the case, you will have to adopt more drastic solutions. The most effective way is to use your moistened wet-and-dry emery paper to remove such smears. Select a paper of similar coarseness to the surface on which you are working (too coarse and you risk leaving obvious scratches - too fine and the area will end up appearing more polished than the rest). Using a small circular motion, begin on the smear itself, and then gradually work outward with ever-decreasing pressure so that your repair blends in with the rest of the surface. A pad of wire-wool with some abrasive paste over the area may further hide the restoration if required

Chips on satinised or frosted glass are dealt with initially as on a glossy piece, stopping the emery-paper process as soon as the surface roughness of the repair matches that of the surrounding area. This is the only time that the emery-paper is sometimes best left dry

|

![]()

|

water damage

Water damage (or water staining) is a superficial (only a few molecules deep) fogging of the surface caused by an actual change in the chemical structure of the glass when a vessel is left containing liquid for long periods. To avoid it happening, vases, decanters etc. should be washed out and thoroughly dried, and rested for a while between uses.

Professional glass repairers and restorers (see under links & useful addresses) can remove water-damage very successfully either by (a) flushing the vessel out with a mixture of hydrochloric and hydrofluoric acids, or (b) mechanical polishing with abrasives on felt-pads, both of which processes remove the damaged 'skin' of the glass. The first process is extremely dangerous, and should be left strictly to the professionals

Mechanical polishing is possible for an amateur

First, you must make sure to remove all traces of limescale, using a proprietary limescale-remover with a stiff brush or wad of wire-wool, then wash and dry your piece thoroughly. You will then need to use your drill, 'pigtail', felt pads and/or cloth-wheel, and abrasives. If you haven't got a power-drill, you may obtain slight improvement by hand, using abrasives on a cloth, but it's hard work

The results of your efforts will probably not be as good as a professional's (although you will get better at it in time), but you will considerably improve the appearance of your piece, and avoid paying the cost of professional restoration, which is generally only worthwhile for more expensive pieces

Some people claim success in removing water damage by using denture cleaners such as 'Steradent', dissolving a couple of tablets in water, filling the vessel and leaving overnight. Since I have not tried this yet, I cannot say if it works or not. I have to say it sounds unlikely to me, although I could well believe it removes limescale. Still, I can't see that it would do any harm

|

![]()

|

chips

Unless these are very small, repairing chips is best left to the professionals, who will do a far better job than you can for a surprisingly small cost.

If you insist on having a go yourself, you will need the following :

Shallow chips on the rims of vases or drinking-glasses are somewhat easier:

All that to save between £3.00 and £5.00? I don't think so!

If a chip is very deep, and to polish it out would substantially alter the shape of the piece, you might consider filling it in instead. This is best done with an opaque resin filler (such as 'Milliput') in the case of opaline glass, or a colourless glue (such as 'Loctite' glass glue - needs ultraviolet light to cure it) in the case of clear glass or crystal. These can both be (a) coloured with dyes or stains before use, (b) carved, sandpapered and polished afterwards, or (c) painted over with enamels or gilded (see enamelling & gilding)

|

![]()

|

scratches

Very light surface scratching can be improved by using your power-drill, hard felt pads and abrasive polishing compounds, and a lot of patience

Serious scratches are another thing usually best left to the professionals

While it is relatively easy, using your whetstones and range of emery papers, to smooth out even fairly severe scratching, it is then extremely difficult for an amateur to restore the original, glossy surface of a piece of glass, or even something approaching it

Indeed, unless you are well-equipped, have the patience of a saint and the skill of an artist, you may well end up making your piece look worse than it did in the first place

Particularly difficult and 'unforgiving' are totally clear pieces (such as much Scandinavian glassware), or pieces with an iridescent finish (which will simply disappear if you try polishing it)

Pieces that are fairly deeply-coloured, however, or which have a casing of clear glass over a multicoloured interior (such as, for example, W.M.F. Ikora-glass) are fairly 'forgiving', and can be successfully polished more easily

|

![]()

|

bruises

Bruises are impact-marks, usually circular, that somewhat resemble bullet-holes in armoured-windows (as seen in most James Bond movies). They are wickedly deceptive. However small they may appear to be on the surface, they always go a lot deeper than you imagine they will, and may spread sideways as well. For this reason, they are best left alone in most cases

If you must have a go, treat them exactly as you would chips

|

![]()

|

stuck stoppers

Theories abound as to the best way to unstick stoppers. Some professional repairers offer a stopper removal service. If you want to try it yourself, use common sense, and go gently. This is how I go about it:

Above all, do not forget that a bottle with its original stopper, even stuck, is likely to be worth more than a bottle with a replacement stopper, so don't push your luck!

|

![]()

|

enamelling & gilding

Personally, we would only ever buy enamelled or gilded pieces which are in good enough condition as they stand. You might, however, have a family heirloom of great sentimental value, but which has seen better days and would benefit from restoration.

Most original enamelling and gilding will have been fired on the piece for permanence. The only enamelling or gilding you will be able to do will be cold, and therefore easily scratched off

Specially made cold glass-enamels can be bought from most craft- or hobby-shops, or stained-glass suppliers, and are available in transparent or opaque colours

For gilding, I would recommend using a metal powder (obtainable from artists' supply shops, and available in a range of colours such as new gold, antique gold, copper, bronze etc). This can be mixed with a little clear varnish, and gives a more permanent result than ready-mixed gold paint, which tends to go dull quickly

If the piece is potentially valuable, you will be better off entrusting it to a specialist restorer of enamelling, gilding and gold-leaf. Some of the general glass repairers and restorers may also undertake this sort of work (see links & useful addresses for a list of some UK restorers)

|

![]()

|

metal mounts

Late 19th Century and early 20th Century glass is often found with attached metalwork of one sort of another. This is usually either solid silver, silver-plated, pewter, copper or brass, and can be cast or hand-beaten. Such metalwork was sometimes to provide strength or improve functionality (rims, spouts, handles, feet, flower-grilles, and hinged fittings for things like powder-pots, inkwells etc), and was sometimes purely decorative (frameworks of flowers or foliage - found most often on Art Nouveau glassware)

The usual method of fixing metalwork to the glass was by using Plaster of Paris. This (a) holds the glass snugly within the metal frame, (b) provides a water-resistant seal, (c) is easily replaceable when it becomes broken or discoloured - or if the glass needs replacing, (d) is a very 'forgiving' material, which can be wiped or scraped away very easily if it gets anywhere it shouldn't, and (e) it allows the glassblowers to work to larger tolerance, as it can be used for filling any size of gap. Plaster of Paris can still be obtained from a Chemist (Pharmacy or drugstore) and is found in most Craft shops. In an emergency, Polyfilla makes a reasonable substitute, but the real thing is better. Although we have come across all kinds of substitutes used by amateur restorers (including various glues, and even fillers for repairing car bodywork!), we would always recommend using the genuine article - mainly because it's easier! Here's how to use it:

(1) remove the old plaster from both the metalwork and the glass. Soaking the piece for a few hours in warm water (a little liquid soap may help) will soften the plaster, and should allow it to be picked out. Unless you can trust yourself to go VERY slowly and carefully, avoid using sharp metal tools, as you risk damaging the metal or the glass. Hard plastic is a safer material to work with - you can make your own tools with it, or buy ready-made sculptor's tools (if the plaster is particularly stubborn, you may have to soak it more than once)

(2) separate the metal from the glass. Once most of the plaster has been picked out, the metal frame will loosen. To separate it from the glass, you may need to exert a gentle 'pull' and 'twist', but be very careful not to overdo it! Do NOT try levering the glass out of the frame with an implement - you will almost certainly break it!

(3) clean off any remaining plaster from either piece, then dry them (if you intend to polish the metalwork, this is a good time to do it)

(4) mix some Plaster of Paris and water to a 'creamy' consistency. If the mixture is too stiff, it will not fill in all the gaps. If it is too loose, it may fall out in places, before it has set

(5) apply the mixture to the metal frame, using a spatula, making sure it gets into all the crevices (a toothpick may help to push it into narrow spaces). Be fairly generous when applying the Plaster mixture - it is easier to remove excess than to later refill gaps you have missed! Now present the glass to the Plaster-filled frame and press it in, gently but firmly

(6) allow the plaster to set. After an hour or so (times may vary), the plaster will be set, but has not yet become completely hard. This is the ideal time to:

(7) clean off any excess Plaster, using plastic or wooden tools. Just remove major excess at this point, and take care not to remove any Plaster from inside the frame

(8) carry out a final clean next day, by when the Plaster will have gone hard, using an old toothbrush. Finally, wash and dry the re-assembled piece

As with any restoration technique, slow and steady does it, and practice makes perfect!

.... go back to to page 1: cleaning

|